Scenes From Home

Fragmentation and Familiarity in Hometeam Gallery's Two-Part Exhibition.

Originally published for Public Display Art, on May 17, 2025.

Homescapes and Homebodies are the names of a two-part exhibition curated by Julia Anderson at Hometeam Gallery, featuring work by artists currently in the Actualize AiR residency. Part one, Homescapes, sparked many conversations, luckily less cacophonic than the interjecting thoughts fueling them. They were mostly with my girlfriend, Onjoli, who is a frequent flyer with me to art walks. An active commentator, Onjoli’s unabashed opinions frequently influence what I write. Her perspective is not positioned toward the arts in the same way mine is—a fact which helps me get outside of myself. Spurred by her comments and questions, I wrote a frank review of Homescapes that you can find here.

Hometeam Gallery. Image by Stefan Gonzales.

It’s important to note that these shows are pop-up, zero-budget productions organized by and for artists who occupy a space that funds free studios for its residents and free events to the public. It is not a typical Pioneer Square art exhibition. While this context does not necessarily change my opinion on the work, it is worth stating.

Homescapes took me on vacation. A series of visitations in scenes of familiarity to each artist were presented through broad processes ranging from leisurely to painstaking. Most of the work hung on the walls; there were three artists whose work took up space three-dimensionally, such as Noel Kat’s highly detailed miniature models of spots vanishing in Seattle—Neon Boots and Vivace Sidewalk Bar—nestled in the front window nook on shelves at eye-level, drawing the viewer in from the sidewalk. Overall, the handling of the various material choices could be identified as having varying levels of craft. For me, the effectiveness of any work of art is determined in large part by the way the craft of the work meets the artist's intentionality (plus, of course, a ton of other things.)

C.M. Ruiz., 'The Picnic Table', 2025, paper collage, 60 x 120 in. Image by Stefan Gonzales.

The collage by C.M. Ruiz had the largest presence physically, though the ambition of scale was undermined by less serious smeared glue marks and jagged edges of cut paper. Onjoli jokingly compared the artist’s process to “adult play time,” a comment which made me feel defensive—defensive for the sake of the creativity in the room, as well as for the playfulness that shows up in my own practice. However, some things at Homescapes did feel exactly like that: falling short of polish, a bit uninvested, while holding so much potential.

+++

Last week, Onjoli and I attended the First Thursday opening of Homebodies, part two of the exhibition at Hometeam. Since the weather has been taking an inspirational turn, the space was packed snug as the 1 Line forty minutes before a Mariners’ game. There was this desperation to enter the gallery. I had to squeeze between socializers to get up close to the work.

Rachael Comer, 'don wasch me or, how to trust your memories and get on with your life', 2025, sugar, wood, epoxy, enameled bathtub. 30 x 60 x 67 in. Image by Stefan Gonzales.

The first thing I noticed was Rachael Comer’s sugary, slippery centerpiece: A bubblegum-pink bathtub, full of vulnerability (and literally water), that anchored the exhibit both physically and in its meaning. I wanted to take a bite out of it. The bathtub is nestled in a partial wooden frame, surrounded by what appears to be tiled walls made of sugar crystals; inside, an abnormally-sized human (a child?) is seated criss-crossed, back to the viewer, head hanging down. It's an evocative scene.

The fractured walls are affixed to a wooden frame that feels slightly too clean to belong amongst the rest. I found myself wanting the fresh two-by-fours to be dusted with sugar entirely, or to be rotted-looking and penetrable. At first blush, I felt they were in sharp contrast to the saccharine setting—the wood so fresh off the rack at Lowe’s, almost begging for more messiness behind the scenes. To my surprise, my curiosity as to how sugar and wood affect each other led me to understand that sugar actually slows the decay of wood; perhaps Comer is leaning into the uncomfortable tension between the clean wood and sugar rot?

Jordan Monloire, 'Mirror in the bathroom install, Collaboration with Saz'. Image by the author.

Works by Drea Harper and Jordan Monloire (a recent Neddy Award finalist) are positioned kitty-corner to Comer’s, and they all just work so well together. The combination of the three exudes a feeling of being behind the scenes, like I'm keeping a secret I want to be free of. Monloire’s beat-up vanity is exactly the same one I had in a busted apartment on Capitol Hill, a domestic vignette embedded with messages scattered all around: photographs pinned to the wall, scribbled notes, partially used balm, and narcan. The vanity was fully arresting passers-by, myself included, all of us trying to read the sticky notes and hanging dog tags, or catch a prolonged glimpse of ourselves in the mirror. Looking at the mirror I shared my own reflection with a portrait of a skin-forward subject I assume is the artist. The photo is developed on a transparent substrate adhered to the mirror, giving the effect that the portrait is embedded in the mirror, like a build-up of weathering. There is a shark toy nestled in the soap holder just below, a cheeky homage to debris-turned-belongings and the collection of memories.

Drea Harper, 'I could see the sadness as a gift', 2025, smocked silk, thread, batting, krazy glue. 84 x 48 x 48 in. Image by Stefan Gonzales.

Harper’s work adjacent to Monloire’s executes a dreamy ruching (a term I only know from RuPaul’s Drag Race). It looks almost as if it is hiding in the corner, disguising itself as a dressing room. The monofilament and tacks suspending the work contradict each other. I wanted either a commitment to the suspension, or to otherwise commit to the contradiction with a sturdy frame. Onjoli enters the waterfall of ruching, as if on cue, and I take a photo. These soft-coded works dig at a deeper nostalgia of memories in a cocoon, riddled with whatever mystery the viewer wants to access.

A recurring theme in both exhibitions is the presence of hair. In the former, Nadia Ahmed and Shannon Hobbs presented sculptures made with clear and white wax embedded with hair. The wax of Hobbs’ shrunken chair—a sculpture constructed of fused candlesticks—contained tiny strays seemingly trapped in the sticky material by happenstance. Ahmed deliberately uses strands of hair to spell out phrases encased in blocks of wax and atop paper doilies: “Honey I’m Home,” “Home at Last,” “Stay for a While,” and “Home Sweet Home."

Kalina Chung, 'Roots', 2025, hair, plasti-dip, clock, wooden box. Photo by Stefan Gonzales.

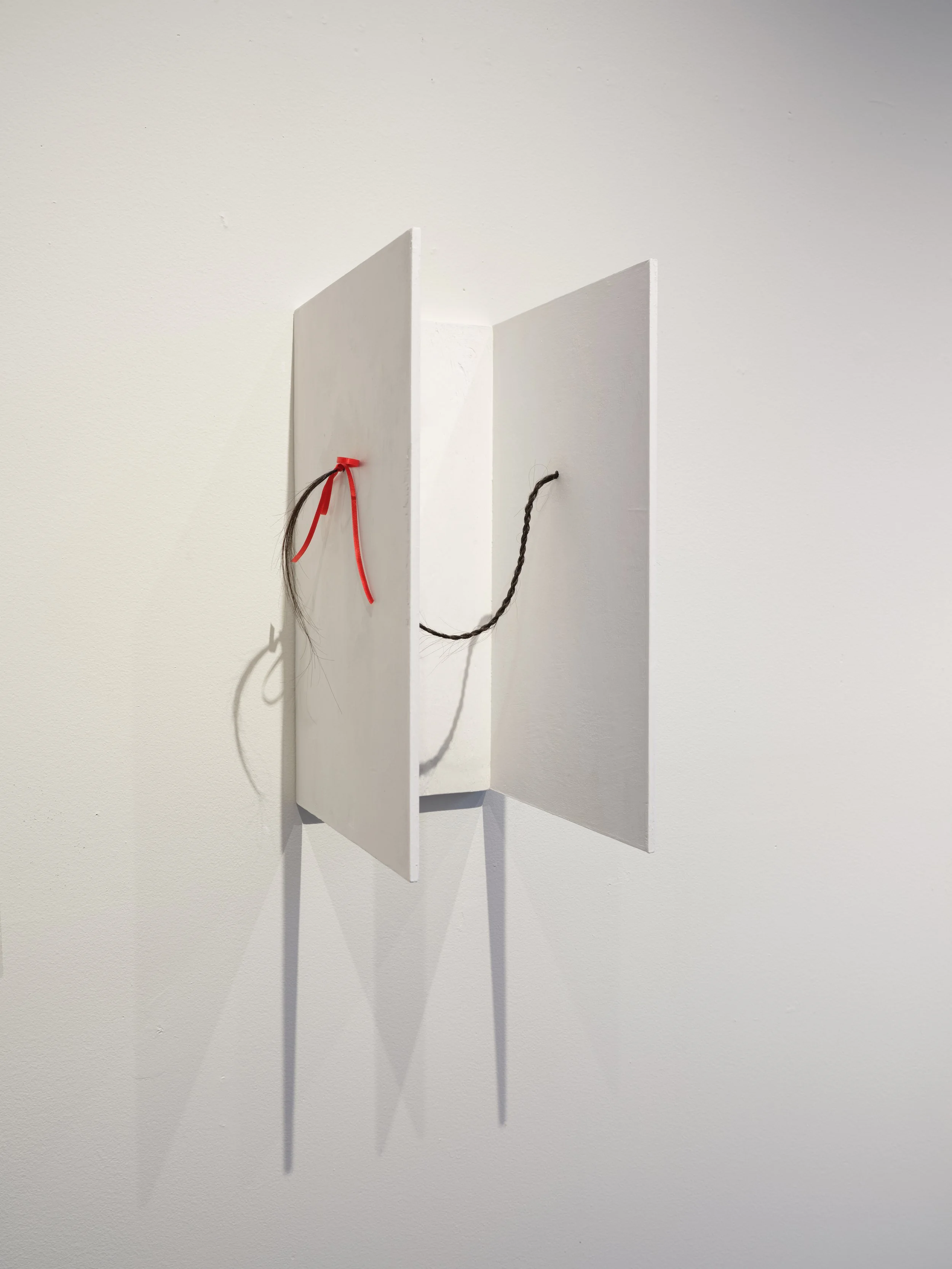

In Homebodies, Kalina Chung uses hair to spin a frame for a clock, lying flat on a wooden box acting as a shelf, complete with golden clock parts in the center. It is delicate and metaphoric next to Lila Thomas’s large-scale painting, a depiction of two figures lounging on couches amid a flurry of leafy monsteras, an embodiment of the exhibition's title. Chung uses hair again across the room, this time more literally: a braid strung between a nook about 5 inches across, made of thin wooden planks, painted white, red bow adorning the ends of the hair sprouting out of the exterior walls. In these instances, one can't help but read hair is an intimate expression and reflection of identity, an indicator of the passage of time (hair growth), and a powerful signifier of one’s identity within society. These themes feel endemic to Homebodies.

Kalina Chung, 'Roots', 2025. Hair, plasti-dip, clock, wooden box (left). Lila Thomas, 'Familiar Rhythms', 2025. Acrylic on Canvas 48 x 48 in (Right).

Kalina Chung, 'Tidy Up', 2025, hair, red ribbon, painted wood. Photo by Stefan Gonzales.

A few works in the exhibition feed a more playful narrative of home. The collaboration between Bridget O’Brien-Smith and Lacey Swain reminds me of a Peter Halley painting with its cheery disposition of color. O’Brien-Smith adorns a stretched quilt by Swain with small, plastic-y blobs of paint all over. Mary Ann Carter’s limp and illustrative sculptures serve as another moment of humor, from her quirky mounted candelabra, to the grounded pointy shoes with an extra dose of quirkiness in the title.

Mary Anne Carter, 'A Note of Encouragement to The Little Girl Who Stayed Up All Night Overworking a Tissue Paper Assemblage in 1st Grade and Went on to Smash Her Sea Otter Diorama in 4th Grade Because It Was Just Plain Ugly', 2025. Canvas, polyfil, plaster, acrylic, and a bunch of crap from the junk drawer. Image by the author.

Another bright spot in the room is a work by Sanoes Stevenson-Egeland, who can seemingly do no wrong in the handling of paint, with a level of determined precision approaching that of a Paint by Number piece. Her works have a graphic, almost flat quality to them in the sequestering of the marks to definite shapes that flood the surface. The subject matter and execution of her text-based painting in Homescapes pushes and pulls at the surface of the scene. A car flooding the viewer's vision with its bright headlights underlays a text written by the artist a few years ago. She works out her own selfishness, trapped in an open-eyed make-out session with death and her own ego. Her vibrant color palettes wash out the imbued intensity.

Sanoe Stevenson-Egeland, 'Ego Death' 2025 Acrylic on paper 16 in x 12 in. Photo by Stefan Gonzales.

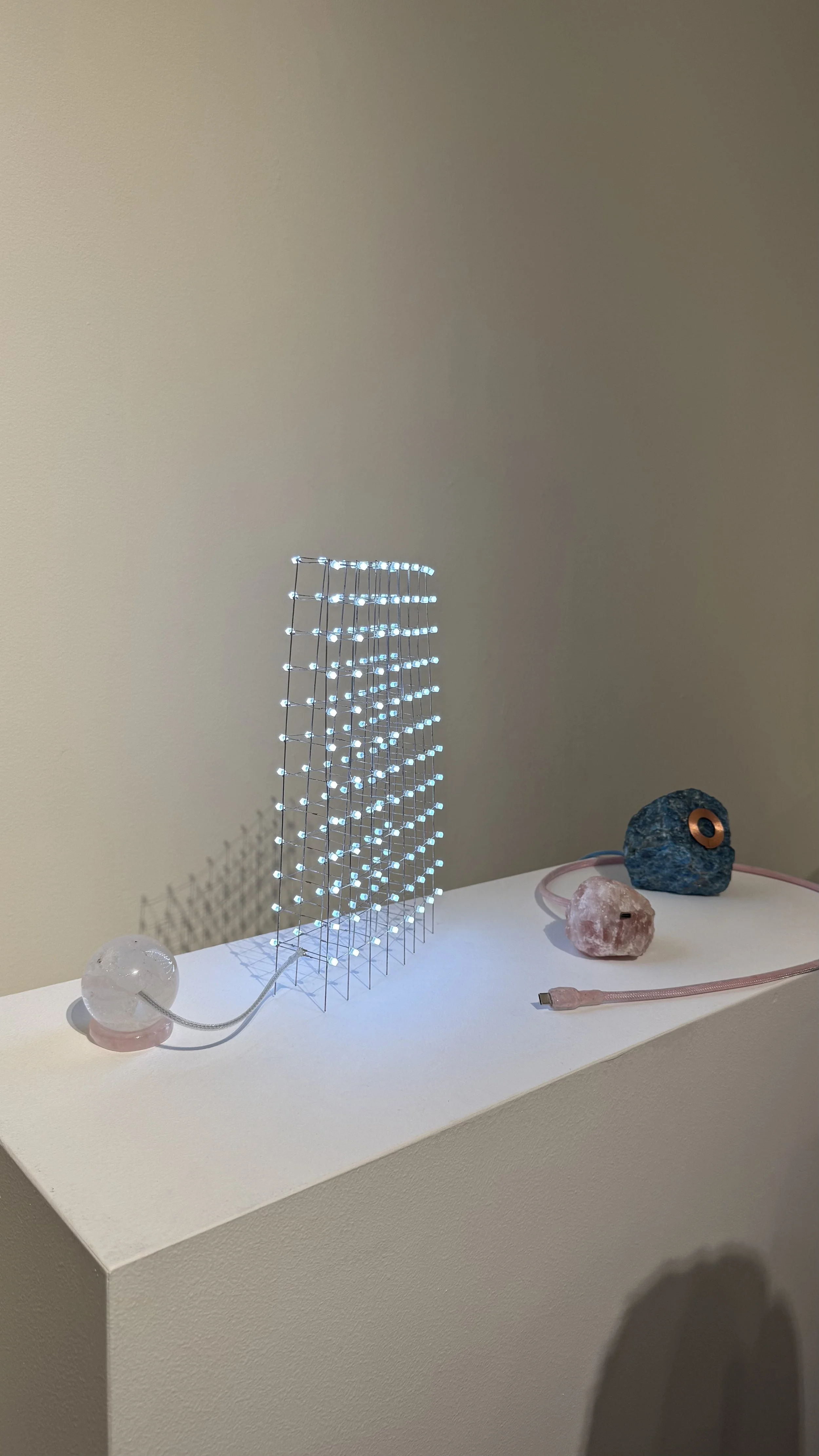

New media artist Kate Bailey is on her own wavelength. I am in awe of her manipulation and nuanced merging of technology and functional art-objects. The work is definitely posturing for a new aesthetic of common household gadgets, a jaunt aesthetically from the other works in the space. At first glance, they seem at odds with the show’s interpersonal theme, but her retro-futuristic works echo a longing for another home, an escape.

Alissa Dymaly-Williams’ video work, Untitled Nostalgia (Remastered), is intended to screen on a tiny tube TV—the kind I had for my VHS tapes as a kid. It wasn’t working the night I was in attendance. I'll return to the space this Saturday, the 17th, for an artist talk at 5pm to see the glitchy video on its intended screen. In the meantime, Williams sent a four-minute clip of the mesmerizing, glitched-out reel, which depicts images of indiscernible people in indiscernible places, abstract enough to project my own memories of the things I can’t quite make out anymore. Even without the video rolling, the tiny tube TV next to Baso Fibonnaci’s steel geometric planter, complete with a live houseplant, did an excellent job of creating a disjointed sense of home in the front window nook of the gallery.

Kate Bailey, 'Plastic Reality 003', LEDs, clear quartz crystal ball, rose quartz stand (rotate orb to turn lamp on/off). Image by author.

Julia Anderson had a ton of artists at her fingertips to orchestrate such thoughtful and diverse ideas of home, both as a place we visit and a place to rest. Ultimately, I found the works to be spirited, determined to embrace the fragmentation thrust upon them. Getting personal can look soft and meticulous, or coarse and quick. These artists spend a significant amount of time with one another and are building their own home with many differing modes of dwelling. Anderson’s ability to weave it all together in this scrappy manner, enduring the parameters of no and low budgets, is a feat that I hope calls attention to the potential of artists and their ability to create critical and energetic discourse.

Julia Monté is a Seattle-based artist and writer. She is a member of SOIL artist-run gallery and a current artist-in-residence at the King County Recology residency. In her writing, she mines her dialogue with others—often her girlfriend—as well as her own internal dialogue to guide the reader through the experience of art spaces. She aims to constructively criticize work while highlighting the abundant creativity and opportunity that surrounds the everyday onlooker.